Guatemala is a Tapestry of Religious Beliefs and Artistry

The rough-hewn stone steps to the whitewashed Church of Santo Thomás were covered with stacks of pottery, wood carvings, towering piles of richly-colored textiles, and perfect flowers. Graceful calla lilies, gladiolas, flame-colored feathery ornamentals and exquisite roses in tight-budded bunches perfumed the warm morning air.

At the top of the steps incense billowed from low pots, filling the air with a resiny scent and smoky haze. Across the square, a bonfire blurred the stairs of its companion church, El Calvario. The two edifices appeared poised in a stony face-off, adding to the surrealism of the scene.

It was Thursday, a typical bustling market day in Chichicastenango high in the Guatemala mountains, a mere 90 miles from the country’s capital, a million light years from the high-tech business-snappy pace I had left behind in the states.

Edgar, a business associate from Guatemala City urged me into the darkened cavern of the church, cautioning me not to offend worshippers by taking pictures.

The scene was astonishing. Hundreds of votive candles flickered on the floor alongside the aisles, marking the way like strobe lights to the altar where a massive crucifix towered.

Village witch doctors (curanderos) knelt here and there in the aisles, performing candle-lighting rituals for good crops, jobs, health, marriage and protection against earthquakes.

“The Catholics are the ones in the pews,” Edgar whispered. “They follow their own, more traditional service,” which I noticed was underway at the altar.

“It really gets interesting if there’s a festival going on in Chichi,” he continued. “The curanderos drink lots of a fermented corn liqueur to heighten their powers, and then they dance wildly in the aisles.”

I was disappointed to miss the wild dancing, but relieved we had arrived after the sacrifice of a chicken, made every market morning as a tribute to a Maya earth mother whose statue sits at a hillside shrine outside of town.

The mystical realm of market day in Chichicastenango and many other highland villages in Guatemala underscores the fascinating range of religious practices in this beautiful Ohio-sized country tucked away in mountainous Central America.

Just an hour’s drive west of these mountains lies Lake Atitlan, the nucleus of an Indian empire as rich as Chichicastenango’s. The 20-mile-long lake, anchored by the dusty hippie town of Panajachel, is ringed by three cloud-frosted volcanoes, giving a first impression of a Buddhistic peacefulness.

Boats leave the Panajachel docks regularly for the prolific weaving villages that dot the shores of the glassy lake. Here, no Spanish is spoken, only the local Maya dialect and, as I was to learn, enough English to bargain shrewdly.

After an hour-long boat ride across the tranquil lake, I climbed the dusty rock-strewn trail to Santiago Atitlan, a volcano-shadowed village where women craft beautiful textiles on ancient backstrap looms.

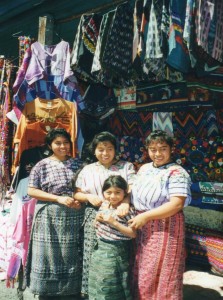

They sell them on the cobblestone streets from rustic stalls draped in a riot of brightly-colored Guatemalan huipiles (blouses), intricately embroidered wall hangings, tablecloths and skirts.

Foraging through what seemed like acres of textiles, I found a beautiful piece covered with dozens of the embroidered Mayan bird figures for which the village is well known. The bargaining process went on for some time, as three women and a young child wrote acceptable sale prices on their hands.

Over and over, they repeated “No, too low” to the counter-offers I wrote on my hand. When we finally agreed on a price, they announced that they didn’t have correct change for my Quetzal bill, so they suggested I take their picture instead, a surprising offer, given Guatemalans’ well-known aversion to picture-taking by outsiders.

The contrasting side of Santiago Atitlan’s textile trade is the village’s worship of the idol Maximon, a black-clad figure sometimes called San Simón.

Maximon combines Judas, Pedro de Alvarado, and the Indian god Mam, and is said to wreak havoc on your enemies.

In a low-ceilinged house behind the town plaza, I visited the life-sized, petrified figure of Maximon, seated ramrod straight in a chair with a huge glass scepter of Christ propped in the shadows.

Maximon’s shoulders were draped with scarves and his face looked like a dried coconut under the hat jammed tightly over his brows. With an eerie dignity, he had a cigar in his mouth, and as I peered at him, his guardians told me he was at least 1,000 years old.

I was encouraged to light a candle and drop a donation in the dish on the floor, which I did out of fear of what might happen if I was added to Maximon’s “enemies” list.

Chicken sacrifices and idol worship aside, mainstream Catholic traditions of Spanish colonialism are still prevalent several places in Guatemala, particularly the large cities of Antigua and Guatemala City.

During the week before Easter in Antigua, religious activities and celebrations are the center of the city’s cultural events, as the faithful host the largest Easter celebration in the Western Hemisphere.

Hotel rooms are booked months in advance by thousands of tourists and devout Catholics who come to the beautiful city from all over the world to witnesses the elaborate processions.

Men, swathed in purple tunics, carry a huge image of Jesus through the cobblestone streets.

Guatemalan women dressed in white, heads bowed under delicate lace veils, follow carrying a hauntingly beautiful statue of Mary.

The hours-long spectacle traverses intricate “carpets” made of brightly-pigmented sawdust and flower petals that have been painstakingly created by town residents the night before the procession.

Midnight mass at all the city’s churches concludes the religious ceremonies the Saturday before Easter Sunday.

When it was time to leave the mystical “Land of Eternal Spring”, I stood in line at the Guatemala City airport, waiting for huddled immigration officers to finalize the vote that would settle the latest of the week’s labor disputes.

I chatted with another traveler, a professor of marketing economics at Purdue University who was a regular visitor to Guatemala and a consultant to the country’s economic development officials.

I asked him why so many of the beautifully crafted products I saw during my visits never made it out of the country. Was it a lack of interest on the part of the consumption-driven outside world?

“On the contrary,” he replied.

“I believe the country needs more of an entrepreneurial spirit. They’re waiting for economic missionaries to arrive and show them the way.”

Economic missionaries would have a good chance at success, I thought, reflecting on the amazing display of art and artistic talent I had seen during my visit. Religious missionaries, on the other hand, would have to contend with witch doctors, chicken sacrifice, and Maximon.

And that was another challenge entirely.